Remember back in school, when they had those hilarious competitions to see who could read the most books during the summer break? Remember how you always crushed the...

What is it about old portrait photography that reaches out and grabs me by the throat?

What is it about old portrait photography that reaches out and grabs me by the throat?

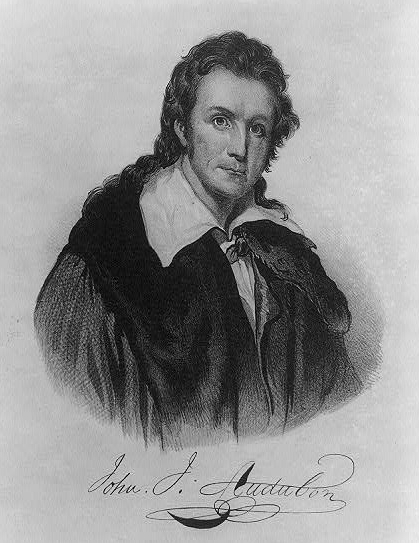

This image to the right has had me in a death grip for days now.

It's a self portrait. The very first "light picture," as it says on the back. Robert Cornelius, a chemist and silversmith in Philadephia, snapped this image of himself outside his father's shop one afternoon in October, 1839.

That's 1839, in case you missed it.

Our man Robert here was a sort of consulting scientist to an early daguerreotype enthusiast who wanted to find a way to shorten the length of exposure needed to create a lasting image. At the time, folks thought you couldn't take human portraits using this emerging bit of technology, because you needed an exposure time of an hour or more.

Not only was it highly unlikely that a human subject could sit still for that long, and avoid the ubiquitous blurring seen in images from this time, but given the amount of light needed on the subject's face, there were concerns of causing blindness.

Robert devised a solution to the problem, then tested it out in the bright sun of a Philadelphia street.

I love the immediacy of his pose, the wind ruffling his hair, the impatience in his eyes and in his crossed arms.

Let's get this over with, let's just see if this works. If it doesn't then I'll try something else.

I think that's one reason why I love this image so much. He's not interested in the slightest in how he looks in the resulting photograph. He's got other things on his mind.

Will this work? I've got a million other things to do. Let's get this done.

I think that's the thing that draws me in so hard. There's no vanity, no stilted pose, no barely concealed fear of the camera and its all-seeing gaze.

The man's got other things on his mind. And it makes you wonder what they are.

In contrast, think about the stiff, formal photography of the Victorian-era carte de visite that we're all familiar with. People sat for portraits for cartes de visites because they needed to, because it was a social necessity. The vast majority of them clearly dreaded the experience. And you can see their discomfort in every carefully held head, every awkwardly averted glance, every sucked-in, corseted gut and plastered down strand of hair.

There's still a lot of that in portrait photography today, in fact.

But the historical photographs that speak the most to me are of people who clearly have more important things on their minds. Usually this takes the form of a politician, or a war general, or something of that sort. These gentlemen had much more pressing matters to concern them, and the emotional toll of these pressing matters easily overcomes any fear or formalism in their poses.

For instance, I have a long-standing and well-documented love affair with Ulysses S. Grant.

I won't go into all the details of why I feel so deeply for him. We can talk about that another time, if you'd like.

But can you look into those eyes, and then away again, without knowing something of what weighs him down?

He is not thinking about the camera. He is not thinking about how he looks.

Even in his more formal White House portraits, where he has clearly been posed to within an inch of his life, he is already out the door and down the street, in his mind. Off doing other things.

But despite my well-known predilection for men in emotional pain, I have readily enough made space in my heart for the impatient, preoccupied, and ultimately mysterious Robert Cornelius.

In the photo, he is thirty years old. In a year or two, he will open one, then another daguerreotype studio in Philadelphia, before moving on to other pursuits and withdrawing entirely from view.

But he still glares at us ferociously from that one sunny afternoon in the autumn of 1839.

And he is so real to me.

Hat tip to Two Nerdy History Girls for introducing me to Robert Cornelius in the first place. What have you done.

Remember back in school, when they had those hilarious competitions to see who could read the most books during the summer break? Remember how you always crushed the...

Ripped from the actual biography of a highly prominent 19th century American figure. Yes, one you have definitely heard of.